Any question ?

Use the Q&A section!

A tool to help you with your legal issues

Legal aspects of energy cooperation are perceived as complex and they may slow down or discourage your project.

The following tool is designed to lower the legal barrier and help you develop energy cooperation projects between potential suppliers and customers in industrial clusters.

If you have a basic concept of the supply and demand in your energy project, you can go straight to the tool below. It is an easy to use fill-in contract template, with explanatory notes at the side. It will help you to bring focus and to agree on the fundamentals of an energy exchange project (sales and delivery). And it generates a ready to use (simple) contract in one go.

You can also approach your project from the general introduction to the contract template, which provides more context, and use the downloads: the contract template, the guide to contract template, and the guide to EU laws.

We also have a user forum, where you can post comments and share tips and tops. We hope that this helps to further our common goal of realizing more energy cooperation projects.

Guide to contract template

1. Introduction

This Guide provides explanatory notes to the R-ACES contract template. Together the Guide and the Template form a practical and simple-to-use legal tool to support regions and organizations to decide on the required legal framework for the supply of energy in their energy cooperation.

The Template can be used as a starting point to develop a solid agreement. For more complex agreements the Guide offers a number of additional clauses.

The Template has been designed with three types of agreements in mind: District Heating, Solar and New Projects. The distinguishing features for the three types are:

-

District heat: volume and profile are determined by Buyers requirement. Price is usually indexed and set periodically. Typically agreements are renewed annually.

-

Solar: volume and profile are determined by Seller’s solar production. Price is often linked to a reference price. The agreement is usually for a fixed duration and special clauses are required to cover changes in subsidies and taxes.

-

New Project: usually includes minimum annual volumes to guarantee cash flows. Pricing can be quite complex and payments are due in case of early termination. Typically these agreements are for a longer duration, and delivery and acceptance sometimes require a detailed scheduling process.

The Template can also be used as a basis for other agreements than the types listed above. The Template has been designed for Business to Business transactions. The user should be aware that household consumers usually have additional protection under EU laws.

The Template has three main parts:

-

Articles 1 – 7 describe the normal process of the energy delivery and payment. If everything goes according to plan, these are all the sections that are actually being used.

-

Articles 8 - 12 concern resolution of issues with the delivery, pricing and external developments. These Articles describe how to resolve the issue, the rights of each party and the financial consequences.

-

Articles 13 -19 provide more or less standard legal and credit arrangements.

To promote standardization this template strives for alignment and sometimes uses identical concepts or wording as found in other generic templates.

1.1 How to use the Template

The Template can be used instantly by

-

selecting the appropriate default clause by ticking the box [ ],

-

completing details in the blanks [●],

-

If required copying specific additional clause from the Guide to the Template; and

-

attaching the relevant Annexes.

The Template is generic and uses the defined terms Energy and Unit. For specific energy and units you would have to do a ‘Find and Replace’. I.e. if the agreement is for Electricity then replace Energy with Electricity and Unit with kWh or (MWh).

Annex 1 contains the definitions and some interpretation rules. Some defined terms, like Buyer Annual Volume, have abbreviations: “BAV”. These are used in mathematical formulas to exactly define the calculations in the Template. In this way any ambiguity, sometimes present in plain language, is avoided.

2. Template key assumptions

Risk allocation: The Template is balanced in terms of risk allocation, without onerous conditions on either side. It assumes a Seller and Buyer of equal standing, unlike the implications of a Supplier and Customer sometimes seen in district heating contracts. Grace periods (to remedy breach of contract) have been set quite strict to ensure that the other party responds timely.

Delivery: The Template does not cover physical transfer of Energy as is the case in delivery of biogas or steam. For those type of agreements quality specifications needs to be defined, and the consequence of not meeting these specifications should be addressed.

Supply only: The Template covers the supply of energy. Joint development and joint investments, cost sharing or cost recovery are typically arranged in other agreements. For details, please see section 3.

Network: The energy is delivered through a system including network and connection. The Template assumes that connection has been installed and will be the contractual delivery point. The Template further assumes that the Seller is the operator of the network and there is no separate network operator. See more background and examples on networks in section 4.

The Template has no specific clauses relating to compensation for installation and/or usage of the connection other than the potential to add a fixed fee in paragraph 3.2.

Laws and Jurisdiction: The Template has been written with common legal principles of the EU in mind. As the Template is developed for Business to Business, consumer protection under EU law is not covered. Also network and access regulation is assumed not to apply. Section 4 gives a high-level overview of the EU laws that could potentially apply to the Template. Also, specific national legislation could apply, especially in the area of district heating.

Technical appendices: The Template covers the basic legal framework for the supply of energy in an energy cooperation. In some cooperation’s a large number of technical details would also need to be specified. Such details can be attached to the template in various appendices. In case of waste heat recover the ReUseheat project and the deliverable “Efficient Contractual Forms and Business Models for Urban Waste Heat Recovery” provides a good overview of some of the technical details [link].

Market Structure: The Template covers the agreement for the supply of Energy from the Seller to the Buyer. The actual market structure for the energy cooperation as a whole may be such that there are many similar agreements. In most cases the Template can be used. The table below gives an overview of the 4 major market structures.

|

Market Structure |

Schematic |

Description |

R-ACES Template |

Example |

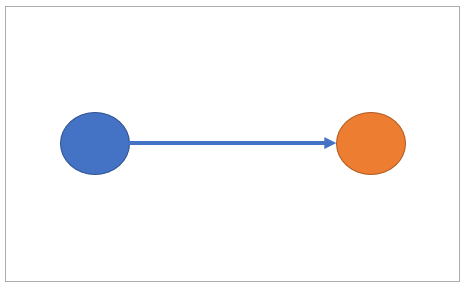

Bilateral “1-to-1” |

|

Direct bilateral contract |

Template can be used | Solar PPA between two parties |

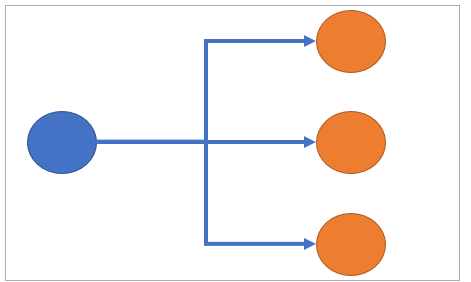

Tree “1- to-many” |

|

One supplier to multiple customers |

Template can be used | H2 plant to multiple customers |

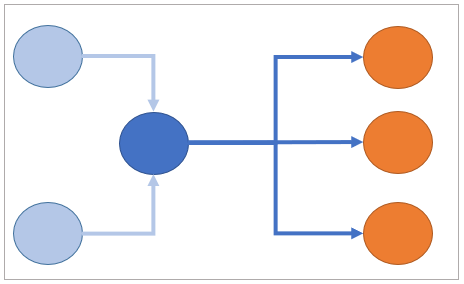

Single Buyer “many to 1 to-many” |

|

Many suppliers to Single Buyer who sells to many customers |

Template can be used | District heating company that buys heat from Data centers |

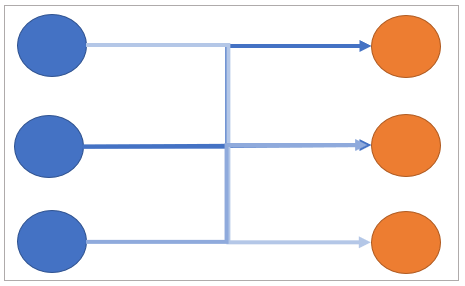

Multiple Suppliers “many to many” |

|

Multiple suppliers to multiple customer |

Template needs expansion with allocation and balancing | Trading and Supply at national TSO systems, including balancing and allocation rules |

Single Buyer: Some District Heating networks may serve several suppliers of Heat. In these cases, usually the largest supplier acts as a single buyer and buys the heat from the other suppliers (e.g. waste heat from a datacenter) and sells it on to the customers. The Template can be used for both selling and buying of Heat by the single buyer. The Heat prices may differ to cover transmission losses and other costs that the single buyer incurs.

Multiple Suppliers: In case an energy cooperation envisages multiple Suppliers delivering simultaneously to multiple Buyers, a number of additional issues have to be addressed. These include the allocation rules of deliveries at the connection point and the balancing risk. Such a system can become quite complex and is beyond the scope of the Template. In case this is of interest, we suggest looking at the contract structure and network codes of Network System Operators (TSOs / DSOs). They cover the relevant aspects as nomination, allocation, reconciliation, balancing, and pricing.

3. Relationship between the Template key assumptions and Investment in Energy Coorperation

Energy exchange projects are often developed by a consortium, willing to invest in production facilities, networks and connections, and/or end-user-installations. Such a project may be driven by numerous business, environmental, and regulatory considerations and can be supported by various legal structures and arrangements. This section of the Guide provides guidance and information on how these joint investments may link to the Template.

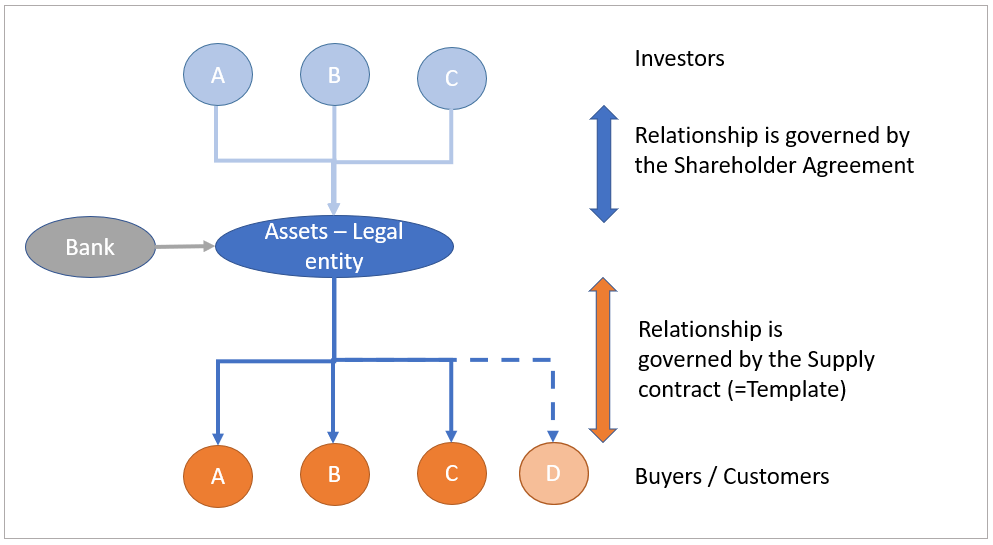

The legal structure can vary. It may include a new legal entity (i.e., an incorporated entity with shareholders that carries out the investment and sales). It can also have the form of a cooperation agreement (i.e., parties agree to cooperate and one of the parties is designated as the operator who does the investment, maintenance and sales on behalf of all partners). The “Guidance on contractual issues for joint services and energy cooperation” of the S-PARCS project provides some additional information on this topic.

This Section assumes an incorporated entity with a Shareholder Agreement (usually in conjunction with the Articles of Association) but the same principles apply in case there is no legal entity and the investors use a cooperation agreement.

A capital investment project is normally based upon the expectation of long term cash-flows from supply agreements, to recover the investments. Most likely, the participants will sign long term supply and transport contracts with the new legal entity, creating a guaranteed cash-flow. The Template can be used for these supply agreements particularly through expansion of the Articles on Annual Volume (paragraph 2.3), Price (art.3) and Term and Termination (art. 5).

Correspondingly, the shareholders must agree between themselves to keep the facilities in operation for the duration of the supply agreements.

It is customary to split the two roles, the role of investor and the role of buyer, into separate agreements. This makes the purpose of each agreement much clearer and easier to understand. The Template covers the supply agreement between the new legal entity and the Buyer and the Shareholder Agreement covers the investment. The split also makes it easier to use the supply agreement for a new customer (D in the figure below) who participates in the offtake of Energy but not in the investment. It also makes it easier to assign the shareholding in the asset separately from the supply agreement.

3.1 Shareholder Agreements

Shareholder (and also Cooperation) Agreements are usually project specific. These types of investments are often structured through a separate legal entity, whose shares or membership interests are owned by the major participants. The agreements usually cover the following matters:

Investment plan, business plan, financing plan. The plans for the project form the basis of the cooperation and will be agreed by the participants up-front. It will cover both the development phase and the operational phase. If project financing is required, the lender will require priority collateral rights over the assets, and over any forward cashflows (i.e. supply contracts, subsidies) which need to be separated for the lender.

Ownership and Governance. The new entity will probably own the assets. The shareholders will normally also share in the risk and reward and have voting rights in the general meeting pro rata their contribution. A day-to-day management should be established with appropriate mandate. Participants should be able to join and leave the consortium under pre-agreed conditions.

Compliance, Taxation, Accounting, Subsidies. Typically, these cooperation projects are not prohibited under competition laws (anti-trust rules) but prior assurance is advised. If the cooperation includes the development of a network that is potentially regulated then a waiver for network-rules may be useful (see EU section on networks). Fiscal and accounting matters often drive the structure, for instance whether the structure should stand alone, or consolidated with the shareholder accounts and fiscal returns. Subsidy application and usage, if any, should be agreed upfront.

Additional information can also be found in “Guidance on contractual issues for joint services and energy cooperation” in section 5 and Annex 1.

3.2 Implication for the Template

There is a potential conflict of interest between the role of investor and the role of Buyer. For example, if the Energy becomes too expensive the Buyer may want to terminate the Supply contract. But then the investment may be impaired as the sales and future cashflows are reduced. It could also be the case that the Asset requires maintenance or reinvestments. If one of the investors refuses to take part, it may endanger the continuity of the Asset and the supply of the Energy. The potential commercial and legal implications and solutions can be very complex and are beyond the scope of the current Template.

However, there are several generic ways in which it may be addressed. First of all, it should be determined whether the investors are expected to remain Buyers in the long term. If so, the Agreement for Sale and Purchase of Energy and the Cooperation agreement can be linked through, for instance, the following clauses.

Cross Default Clause: Basically, this links the two agreements, the energy supply agreement and the cooperation agreement. If a party defaults under one of the two agreements, this counts as a default under other agreement, and the latter may terminate. The defaulting party may have to pay a specific termination amount as included in the agreements.

Material Reason: The energy supply agreement can state that if the cooperation agreement is terminated, this qualifies as a material reason for the Buyer and that the Seller should pay an appropriate Termination Amount. I.e. if an investors wants to terminate his participation in the cooperation agreement he may have to face the pay out of a termination amount.

In general, as it is preferable that investment and Buyers/Sellers role can be disconnected, the predictability of the cash-flows from the supply agreement is increasingly important. As explained in the general part of this Section 3, this can be addressed in the articles on Annual Volume (paragraph 2.3), Price (art.3) and Term and Termination (art. 5) of the Supply Agreement.

4. Guide on EU laws

The relevance of EU law to the Template depends on the Energy supplied. While there are laws at the EU level that regulate Electricity and Gas supply, there is no dedicated EU law pertaining to Heat Supply. Most Member States have national laws governing the supply of Heat. These national laws are to some extent based on the principles of EU Electricity and Gas laws.

The core of the EU Electricity and Gas legislation is a market-based system and the principle that networks are natural monopolies. As networks are natural monopolies, they should be unbundled to avoid any conflict of interest between network operators and producers, suppliers and customers. Anybody should be able to access a network (Third Party Access (TPA)). Networks have regulated tariffs and are licensed by the regulator.

For Suppliers the key benefit of a market-based system is that they can charge the price that they want, the key benefit for customers is that they can choose their supplier. For household customers some additional protection applies.

An energy cooperation usually involves either direct lines or a closed distribution system. These can be exempted from some of the rules in EU Electricity and Gas legislation, which is useful amongst others with regards to TPA rules. An exemption may be useful as it reduces the administrative burden and provides more contractual security. It is not recommended to restrict TPA to the system unless there is a technical reason or capacity restraint, as access restrictions are often opposed by regulators.

District heating and cooling is not regulated at the EU level as such systems operate as “isolated islands” with very limited interconnections. Heat supply is thus regulated at Member State level, and national Heat (supply) laws usually cover tariff setting, and sometimes TPA mechanisms. In the EU Renewable Energy Directive there are also certain obligations on the supplier to provide information to their customers.

Another important aspect is supplier licensing. Supplier licensing is determined at Member State level and is usually also linked to tax rules. In some cases, even in a closed distribution grid, the seller could still be considered a licensed supplier with certain obligations amongst others for invoicing. For protected customers (i.e. households) then the rules in general, and the licensing rules in particular, become stricter.

In major projects REMIT (transparency) might be relevant for large electricity connections.

More information on the EU law can be found in the Guide to EU Law document.